Image Above: Light On The Bay

Location: Erraid Sound, Erraid

The Thaw

Christmas Eve 24th December

Around the gutters and windowsills the movement of water had begun, every projecting surface held a drip tapping out its rhythm on the wet surface of the snow. By late afternoon the drips had found rivulets running unseen under ice. The world had begun to sag uncomfortably, where the snow had concealed it now clung to the skeleton of the island like a piece of linen blown from a washing line. I felt a little sad as if woken from a dream or finding myself falling out of love and realising despite grasping hands that it had slipped through my fingers.

And so the mask has fallen and ordinary objects return to their duties freed from the burden of being a sculpture. The chaos of human existence is revealed in misplaced sandals, spades lodged in garden borders and bags of rubbish abandoned on route to the bin store. I am still not used to snow, it comes from some other place that seems to be governed by pure whimsy. I take comfort that there are still things that even on my best day I could never have imagined.

And so the mask has fallen and ordinary objects return to their duties freed from the burden of being a sculpture. The chaos of human existence is revealed in misplaced sandals, spades lodged in garden borders and bags of rubbish abandoned on route to the bin store. I am still not used to snow, it comes from some other place that seems to be governed by pure whimsy. I take comfort that there are still things that even on my best day I could never have imagined. When the blizzards had began a little over a week ago I had watched the water of the bay stilled and softened by the lightest of touches. I rowed out between snowfalls and felt the change in density the melting iced fronds had brought to this salted lagoon. Beneath the boat a translucence touched with the grey of snow clouds obscured the sea bed. The low water sands and the strand lines of kelp had also fallen for the spell, leaving only the brine as a counterpane to the monotone depths of the sky. The ocean eventually reclaimed the bay. Each incremental rise of successive tides redefined what was given to the water and what belonged to the land leaving a sharp line drawn beneath the whiteness.

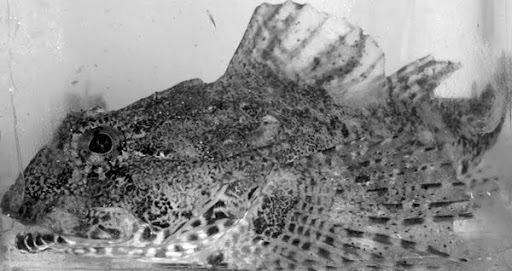

While the snow and ice was barely passable and the tides ran under a full moon we waited for the bay to drain. The sands lent passage and we could deliver Christmas presents to our neighbours, returning with news and mussels plucked from weed drenched rocks. Yesterday I wandered the shallows in the afternoon sunshine as a creature of the tidal race with the hermit crabs and sand gobies for company enjoying the warmth beneath that cold band of snow. Today all has changed and the world seems almost ill-defined, the land runs with water, while the tide carries away small bergs of frozen beachfront.

While the snow and ice was barely passable and the tides ran under a full moon we waited for the bay to drain. The sands lent passage and we could deliver Christmas presents to our neighbours, returning with news and mussels plucked from weed drenched rocks. Yesterday I wandered the shallows in the afternoon sunshine as a creature of the tidal race with the hermit crabs and sand gobies for company enjoying the warmth beneath that cold band of snow. Today all has changed and the world seems almost ill-defined, the land runs with water, while the tide carries away small bergs of frozen beachfront. In the late afternoon the cows return to the byre, their coats wet from a shower trail vapours in the darkness as afternoon turns to evening.

Image Above Right : Coils Of Pea Fencing

Image Above Left: Hay Loft Floor

Image Below: Hermit Crab